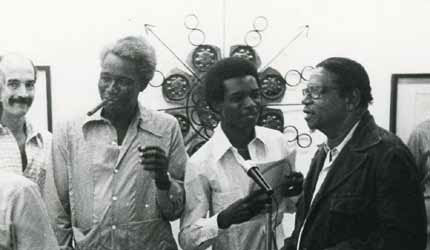

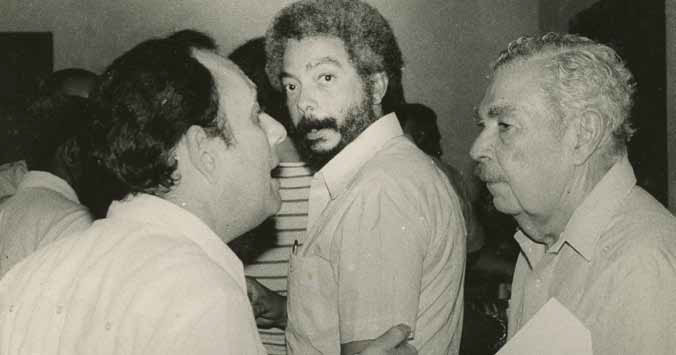

A forgotten visual arts and cultural movement that thrived briefly between 1978 and 1983, Grupo Antillano articulated a vision of Cuban culture that privileged the importance of Africa and Afro-Caribbean influences in the formation of the Cuban nation. In contrast to the official characterization of Santeria and other African religious and cultural practices as primitive and counter-revolutionary during the so-called Quinquenio Gris (a "grey" period of neo-Stalinist censorship during the 1970s), Grupo Antillano valiantly proclaimed the centrality of African practices in national culture. They viewed Africa and the surrounding Caribbean not as a dead cultural heritage, but as a vibrant, ongoing and vital influence that continued to define what it means to be Cuban. Some Afro-Cuban intellectuals, such as the noted ethnomusicologist Rogelio Martínez Furé, proclaimed triumphantly that a "new," authentic Cuban art had been born.

Yet neither this "new art" nor the very existence of Grupo Antillano are remembered today. Grupo Antillano has been in fact erased from all accounts of the so-called "new Cuban art," a movement that took shape precisely during those years and that is frequently associated with the legendary exhibit Volumen Uno (1981). In contrast to Grupo Antillano, however, most of the artists of Volmen Uno did not look towards Africa or the Caribbean for inspiration, but to new trends in Western art. The "new art of Cuba," to use the title of art scholar Luis Camnitzer's famous book, came to be identified with the westernized approach of Volumen Uno, not with the Afro-Caribbean art of Grupo Antillano.

This exhibit seeks to recover the history of this group and their important contributions to the art of Cuba, the Caribbean and the African Diaspora. Several members of Grupo Antillano had attended the Second World Black and African Festival of Arts and Culture (FESTAC) in Nigeria in 1977 and saw their work as part of a diasporic conversation on art, race and colonialism. As Group members stated in their foundational manifesto (1978), "The Antilles are our common real environment... We are not interested in other worlds." They saw their work as part of a long tradition of struggle, cultural affirmation and resistance, what a nineteenth-century Louisiana medical doctor had described as a slave disease: drapetomania. The main symptoms of this disease was an irresistible urge to run away and to escape slavery.

Essentially, these disparate artistic visions point to alternative interpretations of what it means to be Cuban and what constitutes a true national culture. This is, in other words, a debate about what Cuba should be, and how to handle the perennial problem of the country's racial diversity. This debate is particularly intense today, as different social and cultural actors seek to envision Cuba's possible futures and the roles of Cubans of African descent in those futures.

Grupo Antillano fue un movimiento cultural y artístico que prosperó brevemente entre 1978 y 1983 y que articuló una visión de la cultura cubana que destacaba la importancia de África y de los elementos afro-caribeños en la formación de la nación cubana. En contraste con la caracterización oficial de la Santería y de otras prácticas religiosas y culturales africanas como primitivas y contrarrevolucionarias durante el llamado Quinquenio Gris (un período caracterizado por la censura neo-estalinista durante la década de 1970), Grupo Antillano proclamó valientemente la centralidad de las prácticas africanas en la cultura nacional. Para los artistas e intelectuales de Antillano, África y el Caribe circundante no eran un patrimonio cultural muerto, sino influencias vivas y vitales que seguían definiendo el ser cubano. Algunos intelectuales afrocubanos, como el destacado etnomusicólogo Rogelio Martínez Furé, proclamaron triunfalmente el nacimiento de un arte cubano auténtico y "nuevo."

Sin embargo, ni ese arte "nuevo" ni la existencia misma de Grupo Antillano son recordados hoy. Grupo Antillano ha sido de hecho borrado de todos los análisis del llamado "nuevo arte cubano," un movimiento que tomó forma precisamente durante esos años y que se asocia frecuentemente con la legendaria exposición Volumen Uno (1981). En contraste con Grupo Antillano, sin embargo, la mayoría de los artistas de Volumen Uno no miraba hacia África o el Caribe en busca de inspiración, sino a las nuevas tendencias en el arte occidental. El "nuevo arte de Cuba," para usar el título del famoso libro del crítico de arte Luis Camnitzer, pasó a identificarse con Volumen Uno, no con el arte afrocaribeño de Grupo Antillano.

Esta exposición pretende recuperar la historia de este grupo y sus importantes contribuciones al arte de Cuba, el Caribe y la diáspora africana. Varios miembros de Grupo Antillano asistieron al Segundo Festival de las Artes y la Cultura de África y el Mundo Negro (FESTAC) en Nigeria en 1977 y veían su trabajo como parte de una conversación diaspórica sobre arte, raza y colonialismo. En su manifiesto fundacional (1978) lo dijeron claramente: "Las Antillas es nuestro medio afín, real... no nos interesan otros mundos." Los artistas de Grupo Antillano veían su trabajo como parte de una larga tradición de lucha, afirmación cultural y resistencia, eso que un médico de Louisiana del siglo XIX había descrito como una enfermedad propia de esclavos: la drapetomanía. Los principales síntomas de esta curiosa enfermedad eran el impulso irresistible a huir y a escapar de la esclavitud.

Esencialmente, estas visiones artísticas dispares apuntan a interpretaciones alternativas de lo que significa ser cubano y lo que constituye una verdadera cultura nacional. En otras palabras, este es un debate acerca de lo que Cuba es y debía ser y de cómo manejar el problema perenne de la diversidad racial del país. Este debate es particularmente intenso en la actualidad, cuando diversos actores sociales y culturales intentan imaginar los futuros posibles de Cuba y el papel que los cubanos de ascendencia africana jugarán en los mismos.

web design: Los Fieras

proyecto y curaduría:/project concept and curator: Alejandro de la Fuente

Agradecemos a la Fundación Ford por su apoyo para este proyecto /

/ Thanks to Ford Foundation for their support for this project"